HOW TO WRITE A SUMMARY (3)

Task One - Reporting Verbs

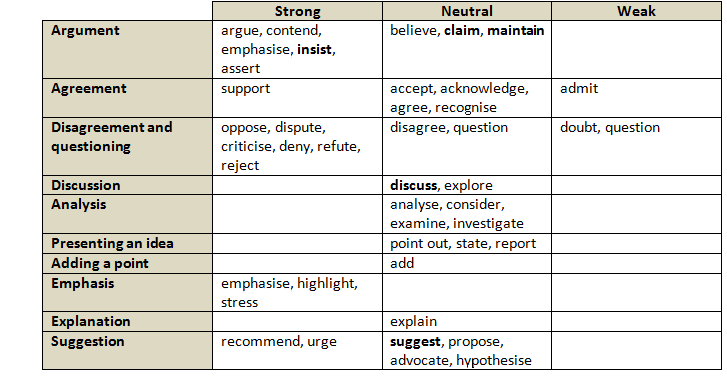

A summary is essentially a short report that contains the key ideas and opinions of a much longer text. To write such a report you may need to identify both the author’s opinion and the opinions of others in the text. Your task is to report their positions faithfully by using reporting verbs that accurately reflect the strength of their opinions.

Look at the reporting verbs used in this summary from ‘How to Write a Summary (2)’.

In the article ‘The Latest Misguided Attack on Sugary Drinks’ Baylen Linneken (2012) discusses the controversy surrounding sweetened drinks, obesity and food policy.

Research published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine claims that sweetened drinks have seriously contributed to weight gain in America and that people of a certain genetic make-up are particularly vulnerable. This conclusion has led to numerous reports calling on the Government to introduce taxes and bans in order to restrict the consumption of sugary drinks. Critics of such policy changes insist that despite a decrease in the consumption of sweetened drinks and of the amount of sugar in drinks over the past few years, the rates of obesity have continued to rise.

Even if sweetened drinks have contributed to the rise in obesity, the author maintains that people have a right to choose what they want to drink and that taxing or banning foods on the basis that they can cause some people to put on excessive amounts of weight is the sign of an oppressive society. He suggests that it would be more effective for the Government to cease its subsidies on the sweeteners themselves; namely, sugar and corn. Ultimately, however, the simplest solution lies with consumers taking responsibility for their own health and making better food choices.

Research published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine claims that sweetened drinks have seriously contributed to weight gain in America and that people of a certain genetic make-up are particularly vulnerable. This conclusion has led to numerous reports calling on the Government to introduce taxes and bans in order to restrict the consumption of sugary drinks. Critics of such policy changes insist that despite a decrease in the consumption of sweetened drinks and of the amount of sugar in drinks over the past few years, the rates of obesity have continued to rise.

Even if sweetened drinks have contributed to the rise in obesity, the author maintains that people have a right to choose what they want to drink and that taxing or banning foods on the basis that they can cause some people to put on excessive amounts of weight is the sign of an oppressive society. He suggests that it would be more effective for the Government to cease its subsidies on the sweeteners themselves; namely, sugar and corn. Ultimately, however, the simplest solution lies with consumers taking responsibility for their own health and making better food choices.

If you would like to learn more about reporting verbs and be able to use them more naturally in academic writing, please go to the series of activities entitled ‘Reporting Verbs’.

Task Two

Read the article ‘Does Fast Food Marketing make Kids Fat?’ by Baylen J Linneken. Highlight the key points and write notes in the column on the right. Your notes should contain some paraphrases, synonyms and reporting verbs. This article appeared on the Web in www.reason.com on 6th October, 2012. When you have finished compare your answer to an example that has already been done.

Reprinted with permission from reason.com

Remove highlights instruction

- Hold down the "x" key, and then click the highlighted text to remove it.

- To remove all highlights, click the button below.

Does Fast Food Marketing Make Kids Fat?Baylen Linnekin (Oct. 6, 2012)Kids recognize the McDonald’s logo better than they do the FedEx logo. Kids are slightly more drawn to the former than to the latter. Obese kids are more drawn to the former than are healthy weight kids. These results are not patently obvious and have important policy implications. These are some of the conclusions reached by researchers at the University of Missouri, Kansas City’s B.R.A.I.N. Lab. A new study by researchers based at the lab argues that the brains of obese youngsters are wired to respond to the logos of food companies. “When showed images of fast food companies, the parts of the brain that control pleasure and appetite lit up,” writes Makini Brice in a summary of the research at Medical Daily. “The brains did not do the same when showed images from companies not associated with food,” including BMW and FedEx. The authors bill their research, published in Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience (SCAN), as “the first study to examine children’s brain responses to culturally familiar food and nonfood logos.” The researchers claim kids rate logos of food companies like McDonald’s more “exciting” and “happier” than logos of non-food companies like BMW. “Food logos,” they conclude in SCAN, “seem to be more emotionally salient than the nonfood logos, perhaps due to the survival salience of food as a biological necessity.” While that finding seems unremarkable, and—I would argue—appears to merit a similarly routine conclusion along the lines of Well, yes of course, the authors see the need for policies to combat this trend. Why? The first clue is the research interests of the lead author, research assistant professor of psychology Amanda Bruce, Ph.D., who specializes in the “neuroimaging of obesity.” And, as the authors write in SCAN, “some experts have cited food marketing as one of the contributors to the recent rise in childhood obesity.” But the most obvious calls for policy changes come from Prof. Bruce herself. “Ultimately, my down-the-road goal is to see if we can help people improve their self-control and make healthier decisions,” Bruce tells the Toronto Star. “Because kids are limited by their underdeveloped brains, however," reports the Star, "that goal would mean asking: ‘How moral or ethical is it to advertise to children?’" The study’s conclusions are “concerning, because the majority of foods marketed to children are unhealthy, calorifically dense foods high in sugars, fat and sodium,” Bruce tells L.A. Times business writer David Lazarus, who took the handoff from Bruce and kept running in the same direction. “Does that mean we should have curbs on junk-food ads, just as there are limits for cigarette and alcohol ads?” Lazarus asks. “I say yes. But I’ll save the free-speech debate for another day.” While I don’t find the SCAN study itself concerning—again, I think it would be stunning if the typical 12-year-old’s brain showed more response to a BMW or FedEx logo than to a McDonald’s logo—it’s probably no surprise that I do find these policy implications inapt. And unlike Lazarus, I won’t save the First Amendment implications of the policy he suggests for another day. They’re unconstitutional. Interestingly, some research that would appear to counter arguments about the particular nefariousness of food advertising and logos comes from a 2010 study by some of the same authors as the SCAN study (including lead author Bruce). That research, published in the International Journal of Obesity, found that obese children are “hyper-responsive to food stimuli as compared with [healthy weight] children.” It also concludes “that many areas implicated in normal food motivation are hyper-responsive in obese groups.” In other words, obese people are probably more likely than is the average person to respond to food imagery writ large—from McDonald’s logos to unbranded cheeseburger photos, and from Gogurt ads to Pinterest donut porn. So it’s not food logos (or ads) that’s the problem. Kids eat what their families feed them. In spite of the arguments of Bruce, Lazarus, and others, policy change in this area should begin—and end—at home. |

MY NOTES |

Task Three

Now practise further the skills of paraphrasing, and incorporating synonyms (as taught in ‘How to Write a Summary 2’)and reporting verbs by writing your own summary of this article in no more than 250 words. Ask a native speaker to check the English for you and then compare your summary to the version that follows in Task Four.

Task Four

Drag the reporting verbs below to the correct place in the example summary.

Copyright© 2012-2013 UGC ICOSA Project, Hong Kong. All rights reserved.